Over the last few years, as newspapers have announced layoffs and closures, one model that's been continually held up as a possible way forward in the future is that of non-profit ownership. The news is a public good, the argument goes, and so it shouldn't be held against the profit motive. Even more, in this time of flux in the industry, removing a publication from the demands of the bottom line allows it more flexibility to innovate and expriment.

The big example that's always held up is the St. Petersburg Times, which is owned by the Poynter Institute, a non-profit dedicated to "everything you need to be a better journalist."

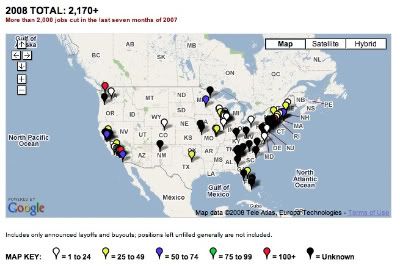

Of course, step one of that "everything" is probably a job. well...

The St. Petersburg Times is offering an enhanced retirement option to some staffers to reduce its payroll and, depending on response, could resort to layoffs later this year. The Poynter-owned newspaper also is imposing a one-year wage freeze for remaining employees.

Oops.